How’s the economy doing?

Your answer to that question will depend on who you are. If you’re the CEO or high-ranking executive of a major corporation, things are going very well indeed. Executive compensation is at an all-time high, and their companies are benefiting enormously from the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, passed in December of 2017.

In the far likelier possibility that you’re not a big-time CEO, well, the picture is not nearly as rosy. In fact, new data show that the gulf between CEOs and their employees is wider than ever.

A Promise Unfulfilled

Since the Great Recession officially “ended” in 2009, the US has been caught in a seeming economic paradox. Unemployment has steadily fallen, labor market participation has slowly risen, corporate profits have skyrocketed, there are fewer and fewer unemployed workers applying for each job, and yet worker wages have stagnated.

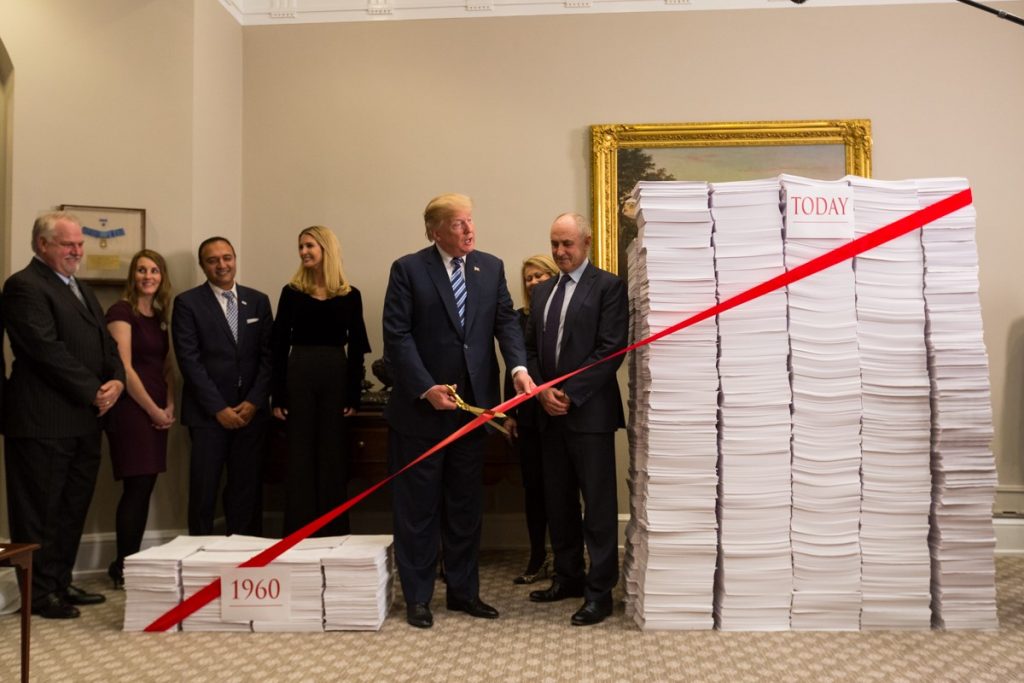

When Republicans passed the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act on a straight-line partisan vote, they sold the bill as an answer to that perplexing question. The big tax cut, which represents the Republican Party’s most impressive legislative accomplishment from their period of unified control in Washington D.C., would give the American people a long overdue raise.

That hasn’t happened.

Oh, the tax cut has definitely worked well for some. Politico reviewed the data and found that many CEOs have made staggering amounts of money selling shares of their companies (which they receive as part of their compensation packages) since the tax cut passed last year.

And huge corporations have responded to the tax cut by embarking on a program of stock buybacks that overwhelmingly benefit richer Americans. Mastercard repurchased $4 billion of its shares last year. Eastman Chemical bought back $2 billion of its own stock.

In all, Americans for Tax Fairness found, Fortune 500 companies have spent more than $238 billion buying back their own stock since the tax cut became law.

Workers Left Behind

However, as critics of the tax cut predicted, the benefits of the cut have not trickled down to rank and file employees.

On average, CEOs now earn 333 times more than the average employee at their company. And stock buybacks do not, as a whole, provide any real benefit to middle class Americans – as the publication Think Progress points out, 10 percent of American households own 84 percent of all shares, while the top 1 percent own 40 percent of all shares.

Put simply, most Americans don’t benefit from stock buybacks because most Americans don’t own stock.

This is part of a larger inequality trend going back decades, a trend which has seen the wealthiest Americans scoop up an ever-larger percentage of the nation’s wealth while the remaining 99 percent have, essentially, not received a raise during that time.

Possible Solutions

These dynamics have been at play for so long that we tend to take them for granted. We just assume that CEOs will make staggering amounts of money, that big corporations will ignore their workers and single-mindedly pursue short-term profits and that wages will remain stagnant.

But these are not inevitable results of a market economy. They are the results, at least in part, of conscious policy decisions that have been made over the last 40+ years of American politics. And they can be reversed – or at least blunted – by other policy decisions.

Senator Elizabeth Warren (D-MA) – widely considered a frontrunner for the Democratic presidential nomination in 2020 – has put out a plan that attempts to re-orient the incentives and outlooks of large corporations. It will do this, in part, by legally mandating that US corporations allow their workers to elect 40 percent of their board of directors.

That policy – known as worker co-determination – is already in effect in Germany and other western European countries. And it polls shockingly well – new analysis indicates that worker co-determination has greater than 50 percent support in literally every congressional district in the country.

That number is likely to decline as worker co-determination becomes more of a legitimate possibility, part of the country’s partisan battle, and not just a wonky policy idea introduced in relative anonymity. But there is, at the very least, good reason to believe that populist, worker-centered economic policies can find support with constituencies that don’t usually vote for Democratic candidates.

Leave a Comment