Shihan Qu, of Zen Magnets, who says magnet balls are “like magic”, was uniquely successful in overturning the Consumer Product Safety Commission’s regulations on neodymium or rare-earth magnets in a 2016 court ruling.

During the subsequent three years, there have been six times more magnet ingestions or 1,600 cases this year, the Washington Post reports.

In 2014, the Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC) approved a national safety standard for rare-earth magnet sets, popular among adult scientists, requiring that individual magnets sold either be too large to swallow or have a magnetic force below a specified threshold.

The CPSC’s guidelines customarily stand.

However, in an exceptional ruling in 2016, the 10th Circuit Court of Appeals including then-Judge Neil Gorsuch, overturned the first CPSC ruling in 32 years, handing the industry a stunning deregulatory win.

Poison.org reports that, “when two magnets are swallowed, they attract each other and meet each other within the child’s body, causing digestive tissue to be trapped between them or boring holes in organs.

This cuts off blood supply to the stomach or intestines. These internal injuries can be life-threatening.

Similar results occur when a child swallows even one magnet, Poison.org reports.

Voluntary Standards

The rare-earth or neodymium magnet industry is snowballing now that manufacturers are free to issue voluntary safety standards, ostensibly based on both customers’ preferences and safety requirements.

“However, manufacturers decided they would only consider standards that don’t change the utility, functionality and desirability of the product for adults,” Craig Zucker, whose company, Maxfield & Oberton, makes Buckeyballs that compete with Qu’s Neoballs, told the Washington Post.

Zucker’s annual Buckeyball sales totaled $18 million by the end of 2012 and he controlled 90 percent of the magnet ball industry.

In July 2012, the CPSC sued Zucker.

The following month, the consumer agency sued Zen Magnets.

The two suits were the agency’s first in 11 years.

Since Zucker held the lion’s share of the market, he settled for $375,000 to cover a recall, bankrupting his company (although he’s back in business again) and leaving Qu as the only man standing, HuffPost reports.

The other magnet vendors had already fled the market by this time.

Qu, who immigrated to Colorado from China when he was 3 years old, vowed he would never settle.

In March, 2016, Qu won his resounding 10th Circuit Court victory killing the rare-earth magnet regulations.

Swallowing Incidents Insignificant?

The 10th Circuit decided magnets aren’t defective just because they act like magnets and stick together.

Or as the court put it: “The attractiveness of the magnets to each other is the sine qua non of their essence. Without the ability to attract each other, the product is worthless.”

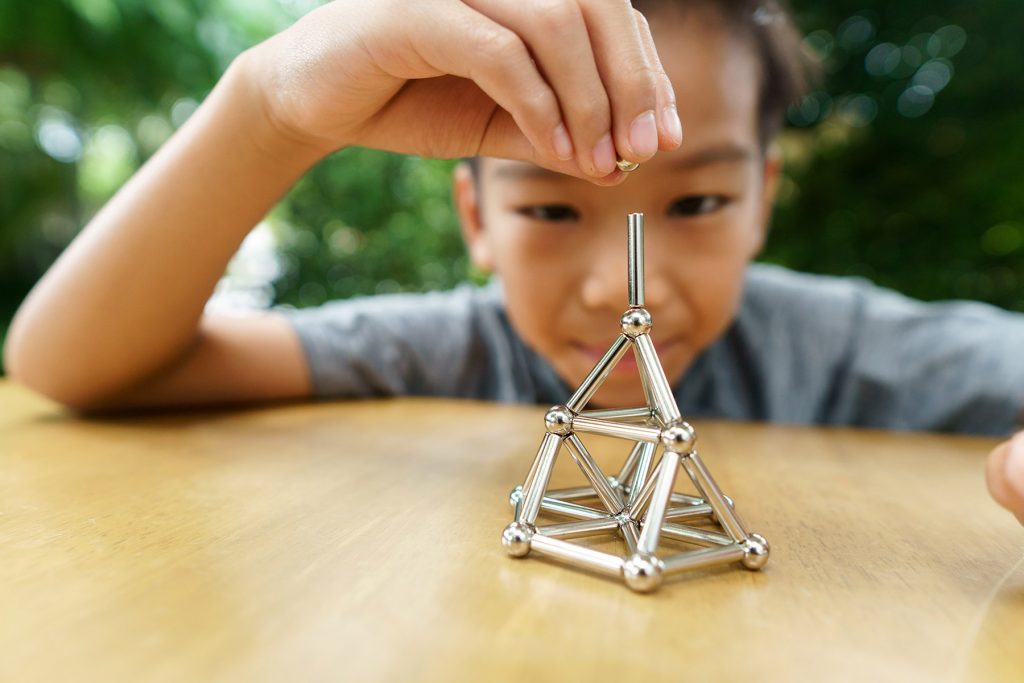

The court also found the magnets did have utility, even if only to spark interest in science and said warnings and protective packaging were sufficient to warn parents of product hazards.

Siding with industry over children, the court decided the estimated several hundred swallowing incidents per year–the most the CPSC could claim to show, and a number that included all brands of magnets, not just Zen Magnets–was ‘insignificant’ compared to the millions of magnets sold, especially where there was little evidence linking any particular injury to Zen Magnets in particular.”

Most of the injuries were only “possibly” connected to the product and the Consumer Product Safety Commission had given too little thought to how useful magnets were for scientists, the court stated.

November 21 Phone Call

On November 21, the magnets committee held a conference call that a Post reporter listened in on with the committee’s knowledge. The committee members were close to finalizing the wording of a voluntary standard they could all agree on.

The Post reported, “the magnets committee began with a focus on using warning and packaging to prevent accidental swallowing by children. But then it explored other ideas.

“One person suggested moving away from spherical shapes. Another wondered whether colored magnet balls looked too much like candy.

A gastroenterologist, Bryan Rudolph, brought up size.

“How large would those have to be in order not to be swallowed?”

The answer was 1.25 inches in diameter–a little smaller than a ping-pong ball, but also six times larger than the existing magnetic balls.

“Why not try making them too big to swallow? Rudolph asked,

“Because nobody would follow it,” Zucker replied.

In early December, the voting members of the magnets committee received a ballot containing a proposed voluntary standard for magnet sets. The votes are due in early January.

While warning labels and protective packaging are expected to be required, the magnets themselves are expected to be just as small as ever, The Post concludes.

Leave a Comment