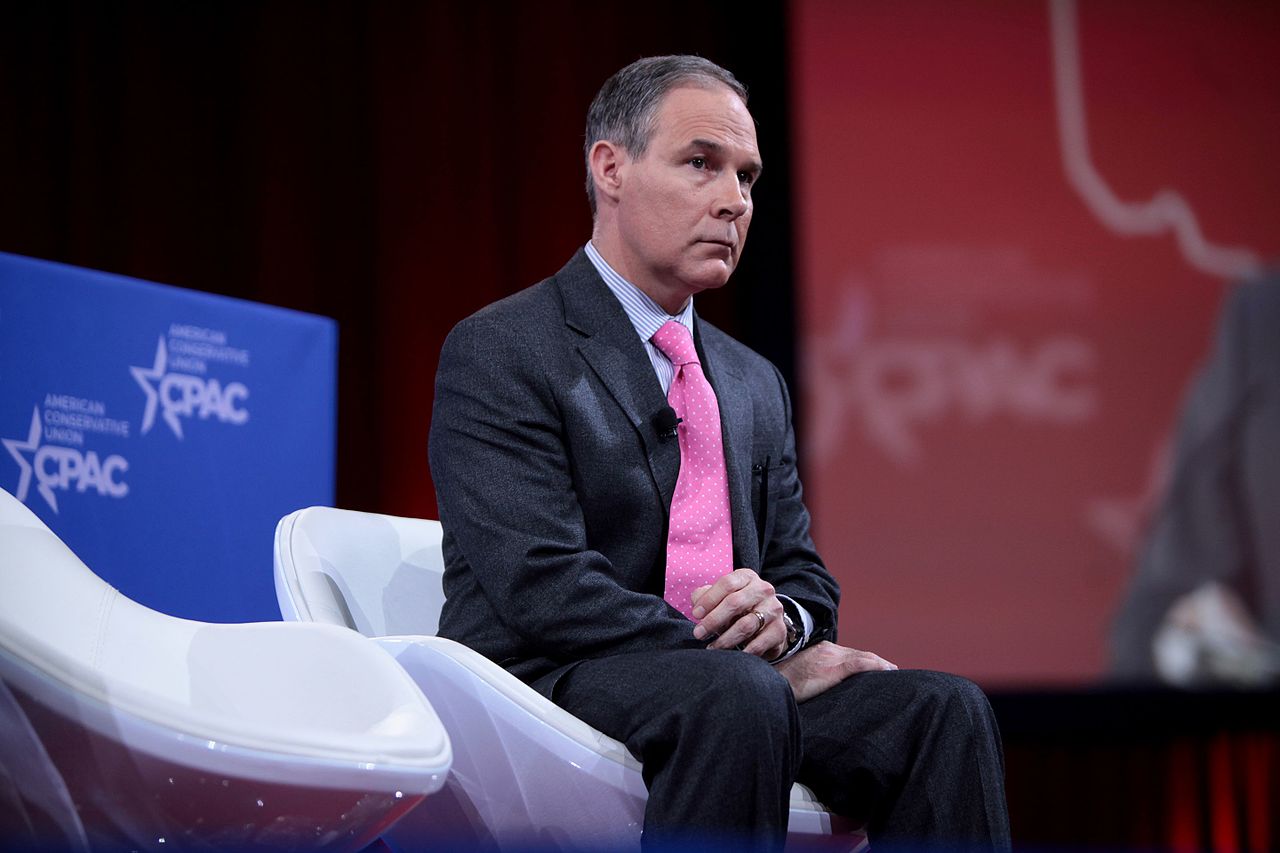

Photo Credit: Gage Skidmore, Creative Commons 2.0

At the beginning of March, EPA Administrator Scott Pruitt announced plans to chuck environmental regulations pertaining to the handling and disposal of coal ash, a substance that contains a number of carcinogens.

Despite the obvious dangers, Pruitt and the EPA said nothing of the public health risks in their announcement earlier this month. Using his signature rhetoric, Pruitt argued that repealing the coal ash rule would allow states to have more autonomy in how they regulate electric utilities and independent power producers. He said nothing however of the influence of the industries themselves who successfully lobbied against the regulation last September.

Health Risk

As mentioned, coal ash is composed of a number of carcinogens, including lead, arsenic and selenium. As such, it is highly hazardous to live anywhere near a coal ash depository. Those that live within a mile of these facilities are exposed to the same health risks as those who smoke a pack of cigarettes every day. It follows then that these residents are far more likely than people who live in clean-air areas to contract cancer later in life.

Opposition

Lisa Evans, an attorney for EarthJustice, spoke directly about this regulatory blind spot in the current administration’s environmental policy: “This is the second biggest toxic pollution threat in our country, and we need to clean it up – not make things easier for polluters.” She continued, “People living near more than a thousand toxic coal ash sites are at risk. They face contaminated drinking water, toxic dust in the air, and serious health threats just because the EPA is choosing to side with polluters over the public.”

Pruitt

By contrast, Scott Pruitt focused on state autonomy and the alleged economic benefits of a repeal: “Today’s coal ash proposal embodies EPA’s commitment to our state partners by providing them with the ability to incorporate flexibilities into their coal ash permit programs based on the needs of their states.” He went on: “We are also providing clarification and an opportunity for public comment – something that is much-needed following the public reaction to the 2015 coal ash rule.” The press release also noted that rolling back these rules could potentially save the “regulated community between $31 million and $100 million per year.”

Litigation

The original rule, introduced in 2015, never saw the light of day, due to major pushback from the regulated industries. It is currently pending in the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit. The rule proposed by Pruitt would address four provisions remanded by the courts, in addition to some other sections that were identified in public comments.

The Actual Proposal

The EPA’s new proposal – which amounts to deregulation – would allow states to pursue their own “alternative risk-based groundwater protection standards,” where it can be shown that the company being regulated does not have a maximum contaminant level (MCL). It also asks for feedback as to whether a company should be allowed to seek out their own standards with the help of a “professional engineer.” Of note is a suggestion that states be allowed to loosely monitor companies that fail to implement adequate lining in ponds containing coal ash. Under the Obama-era rule, facilities handling coal combustion residuals (another name for coal ash) are supposed to cease operations immediately if there is a breach in the ash pit’s lining.

Lining

This last point is significant since CCR is generally stored in wet ponds. If these storage units are left un-lined, the coal ash can leach into the soil and eventually into proximate groundwater. Needless to say, inadequate lining (or no lining at all) can have disastrous consequences for nearby water sources. Nonetheless, the US government has left coal ash pits virtually untouched. It was only until recently that rules were introduced to prevent groundwater contamination, leading companies like Duke Energy Progress to describe “the lack of a liner” as “a feature, rather than a flaw.” An attorney representing the company said their pits “were built more than a decade before the adoption of any federal or state regulation related to groundwater corrective action.”

For now, Pruitt’s proposal is just that: a proposal. It will have to undergo a 45-day period of public comments before it can be implemented.

Leave a Comment